Zein | He/Him

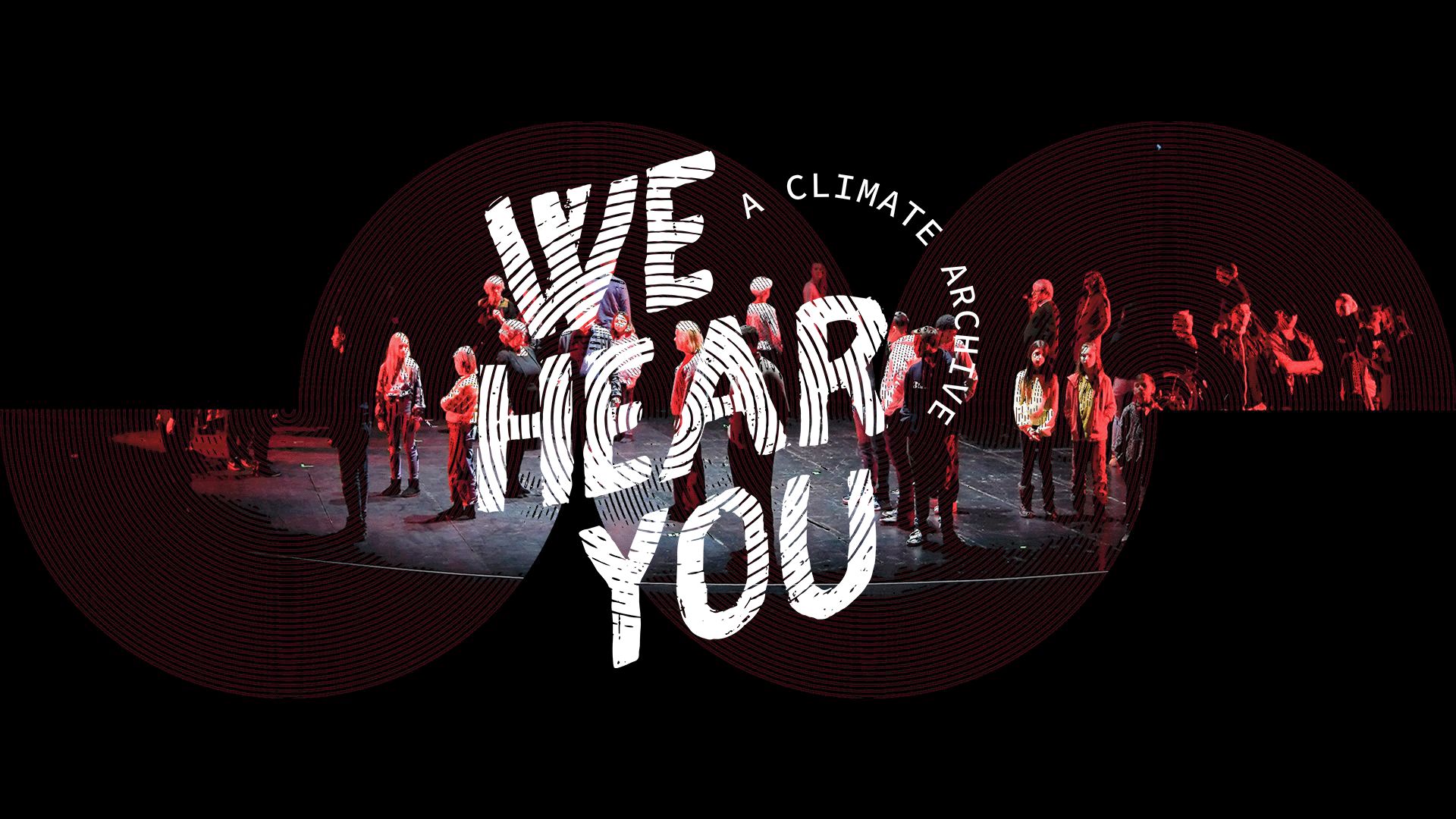

The Sea Inside Me: An Intimate Portrait of Life, Love, and Activism

Alexandria, Egypt

Flooded Grasslands and Savannas

Mediterranean Forests, Woodlands, and Scrub

Session 5: February 2, 2023

I’m here to tell you a story—my story. I come from a city nicknamed “the bride of the sea.” The sea is everywhere to me. My childhood was by the sea. My first love was by the sea. Even my sad moments were by the sea. I’ve cried to the sea many times.

But my relationship with the sea started during fishing trips with my grandmother. We would sit on the tip of the pier, and I would eagerly wait for the next catch. She would teach me her little techniques and tricks for fishing, and after a good day, I would take a dip in the sea. I would feel it engulfing me, containing me. “I’m here. I’m with you. I love you,” it would say.

And then, as the years went by and I grew older, the weather grew harsher. In the winter, the rain and the sea would flood my streets, affecting the lives of many. I was so confused: why was this happening? Even then, it wasn’t until my friend confided to me that he had attempted to take his own life by drowning himself in the sea that I was filled with despair and sadness.

I decided to confront the sea: “Why are you doing this? Why are you hurting us?”

As the waves crashed loudly, I could hear a distant cry from the sea. “I’m hurting. I’m dying. Help me!”

That’s when I decided to play a role and take action. I decided to pursue environmental health and pursue a career in tackling the climate crisis by fighting for the health of the people and giving voice to the voiceless. And from policy paper to policy paper and from one conference to another, I’ve learned that what seems to be a battle against climate change is actually a battle against each other.

The years pass by. On my way to the next climate conference, I see an ad: “Be the first in 2085 to see the Library of Alexandria underwater. Book now for only 300k!”

Suddenly, I just freeze. I stare blankly at the ad. Flashbacks of my memories with the sea. My childhood, my life, my home. What was once Alexander the Great’s dream now becomes a collective dream of all its people.

Zein is a 21-year-old medical student from Alexandria, Egypt, who is motivated by his love of activism and faith in a better future. Zein uses his strong connection to the Mediterranean Sea as motivation to advocate for climate action and health. He firmly believes that art and storytelling have the capacity to affect change in the most profound ways and is driven to use his creativity to inspire and engage others, working towards a healthier and more sustainable future.