Lyndi | She/Her

The Comma

Texas and Washington, DC, USA | Tibet

Montane Grasslands and Shrublands

Temperate Grasslands, Savannas, and Shrublands

Session 3: December 12, 2022

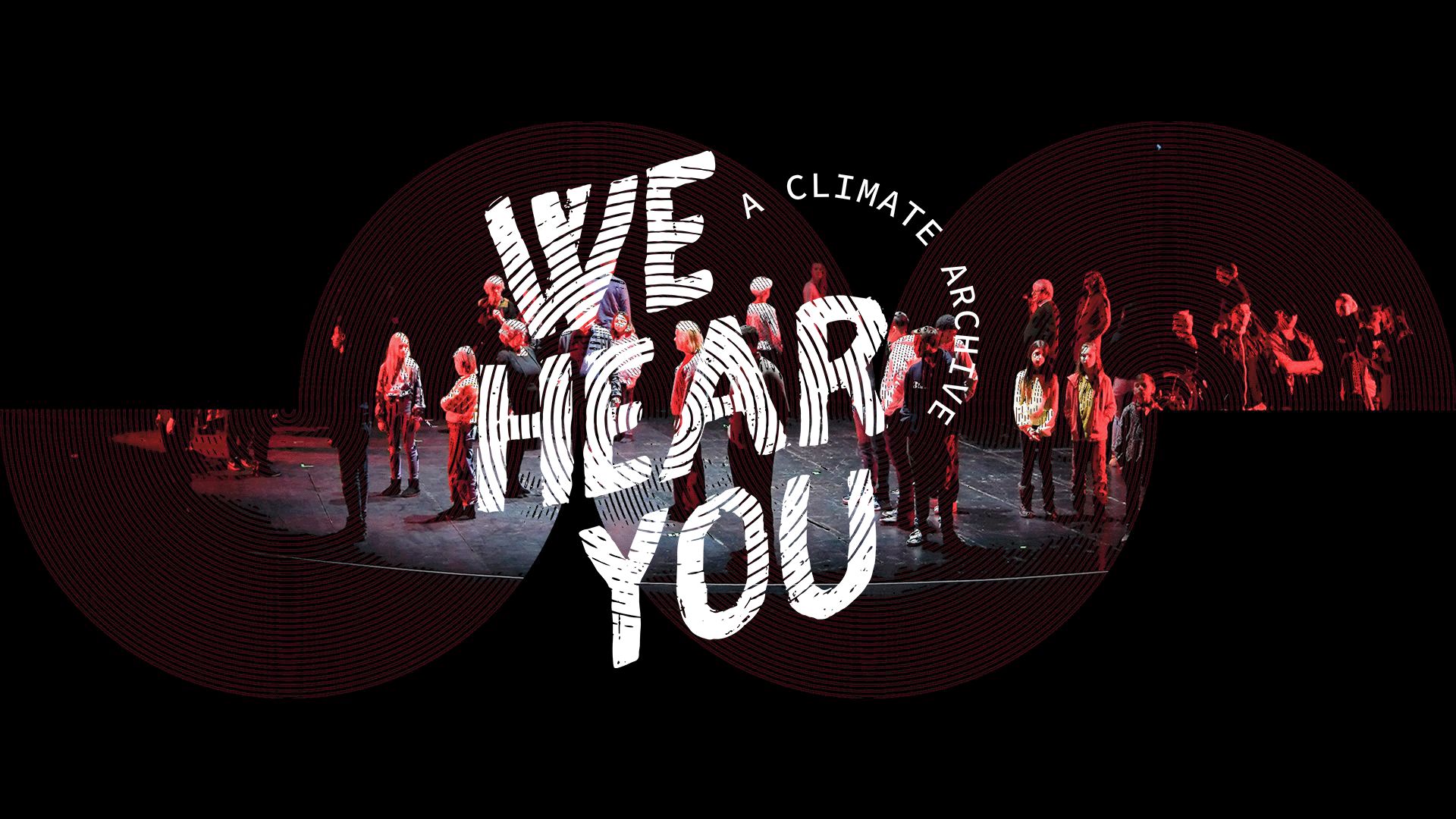

I remember walking into the We Hear You launch performance last year, here in Washington, DC. The performance took place within the climate photography exhibit Coal & Ice at the Kennedy Center. And I remember being struck by the stark, bright, some of them kind of startling images, seeing people’s faces and landscapes—and all of them being looked upon by a crowd of people who came from, I think, positions of privilege that we are often probably not adequately aware of.

I settled into my seat ready to see some of the artists tell their stories—very similarly to how we are today—and in the background, projected on a screen behind the stage, was a beautiful picture of Mount Everest, which is the tallest mountain in the world and in the Himalayas. And I just remember feeling a little ping, like a little knot somewhere—you know, that you can sometimes feel in your stomach—when I looked down at the bottom of the picture and saw that it said “Tibet, China.” (read aloud as “Tibet comma China”)

And I remember that comma. And I remember thinking, “Wow! We’re in a space with so many people in positions of power, listening to people’s stories of indigenous contexts that are being washed over, and yet we’re still in a space where we have to include that comma.”

My father grew up in the Himalayas in a home we know as Tibet without the comma, in a home in a small town called Qüxü, with a family whom I’ve never been able to meet in person. My father always talked about the rivers, the mountains, the valleys that he grew up in about thirty minutes outside of Lhasa. And he always tells us this one story about how he and his brothers and his friends would swim absolutely naked in a river that would come down out of the foothills, called Yarlung Tsangpo, and the water was so clear you could just put your hand all the way to the bottom and still see it.

That was unimaginable to me growing up in central Texas, near water that you could definitely not see the bottom of. In our creek, with drought striking every year, we were lucky if water was even there. But my father’s story always felt so vivid in my mind.

And I remember just sitting there at the performance looking at the mountains, and the first feeling that came after that initial pang was a little bit of a feeling of guilt, almost. Who was I to feel sad about a place that I had never even been able to find my own way to? But then the feeling that came after was anger. Because it wasn’t my fault that I’ve never been able to go.

But even still, it’s… it’s so hard sometimes to try to wrap my mind around feeling connected to a place and to a space I’ve never been to, and a place that, you know, used to be normal, and used to be my father’s normal and everyday. I think he never knew that one day he wouldn’t be able to go back. And that makes me think that you just never know what’s normal until it’s gone, right? Like maybe someday, my normal right now, maybe the little river behind my parents’ house now in central Texas, or being able to just walk outside and walk down the street, wearing whatever I want to, or breathing in the air the way that I do, will be a story that I just pass on to someone who will hold onto it and grow an identity around it, in the same way that I have around that river and the mountains and a space that I’ve never gotten to witness in person.

Lyndi is a JDEIA (Justice, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility) research analyst at the United States Institute of Peace and an Asian Studies graduate student at Georgetown University. She is also a biracial Tibetan-American, a performer, a creator, and a seeker of justice in the tide of global politics.