At the root of my story is a weight of responsibility, a duty that rises from the ashes of conflict and violence. I’ve walked among the shadow-dwellers of war in Kyiv—a war stoked by an insatiable thirst for fossil fuels. This war is the cruel child of human hubris. It has ripped through my homeland, shattered my dreams, and etched indelible scars on the canvas of my innocence—just as it has for many of my friends.

Yet amid the echoes of this past, I found my purpose, my call to arms. I did not take up guns or grenades. Instead, my weapons became my words, my resolve, my belief in a cause that transcends my personal suffering. I began my crusade against an enemy that recognizes no borders, no treaties: the looming specter of climate change. My voice, once silenced by the thunder of war, has now become a clarion call for climate justice—a call that has found resonance within the collective consciousness of humanity, or at least of my movement.

As we stand, on the verge of an environmental catastrophe, the question I often hear is, “Why do you continue? Why do you continue to strike for climate while there is a war in your country? You’re not a warrior. Warriors are on battlefields. You’re a coward.”

But cowardice, I believe, lies in doing nothing. The answer is rooted in the rings of the past and the seeds of our shared future. When I lift my voice, join a strike, or challenge the status quo, I am speaking for my people, whose pleas for mercy have been drowned out by the destructive catastrophes set in motion by the fossil fuel industry.

I strike for my homeland: a theater of past and present violent conflict, now also standing in the shadow of rising seas and searing heat waves. I strike for our world as we know it, teetering on the brink of irreversible climate disasters, straining under the weight of our collective indifference and inaction. But the strikes, the protests, the tireless campaigns, they are not just about mitigating climate change. They’re about something far more profound: justice. Climate justice that transcends the boundaries of nations, economies and ideologies. Climate justice that recognizes the unequal burden of climate change, where those living in the Global South bear the brunt of the impact despite contributing the least to its costs. Climate justice that demands reparations for these nations seeking climate finance and debt relief to help them emerge from the devastating consequences of our warming planet.

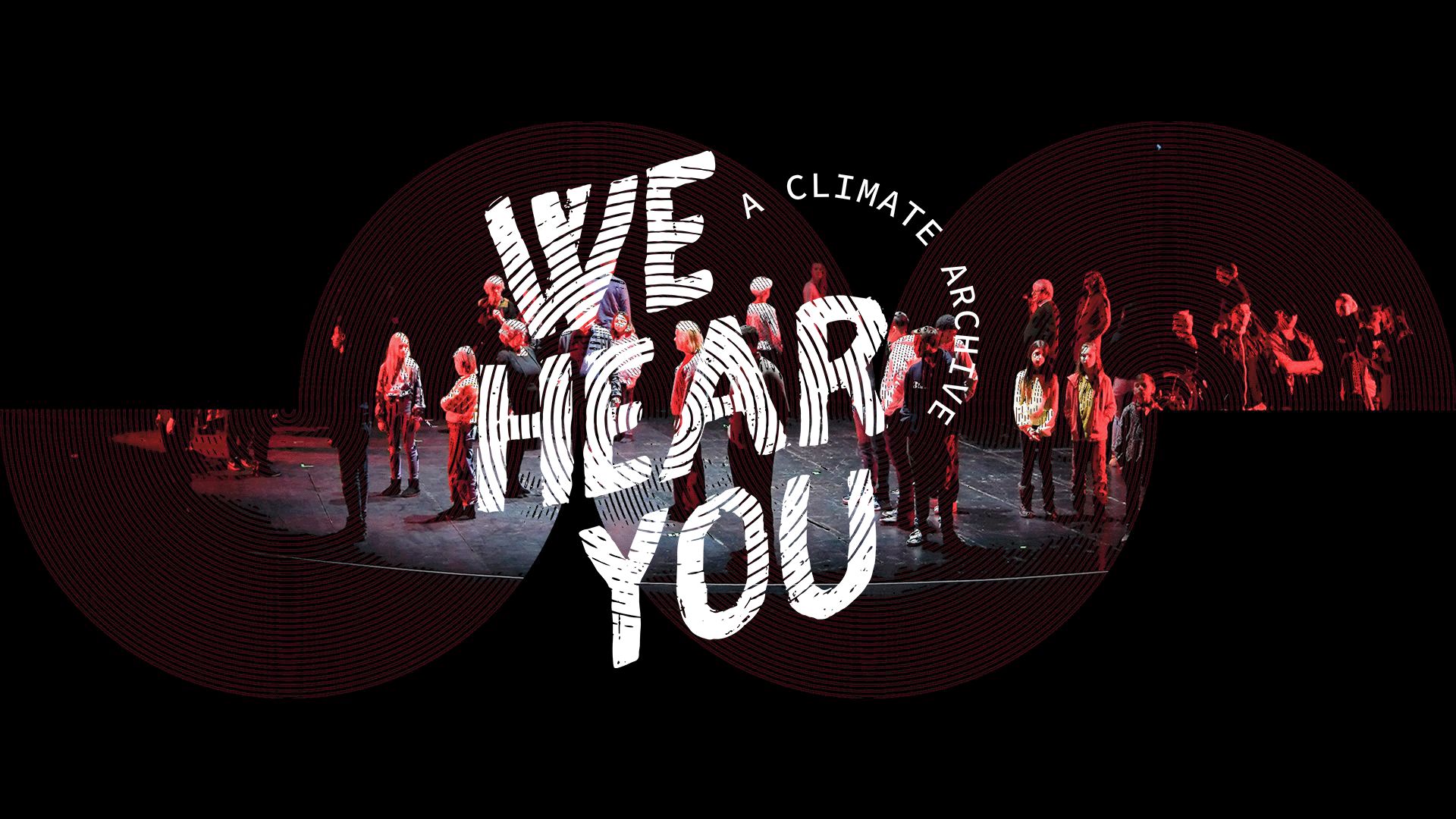

Since March 2019, when our movement emerged, I have been walking shoulder to shoulder with my friends on the streets of my hometown, Kharkiv. We have been demanding an equitable future, a safe and just life for everyone. But where are my friends right now? Thirteen of them have lost their futures, just as they have lost their lives in this war.

I strike for a world where climate justice isn’t just a slogan waved on a sign, but a tangible, achievable reality. A reality where the rights of our planet are linked directly with the rights of its people. Where sustainable practices triumph over corporate greed, and where green technology is the heartbeat of our global society. I do not walk this path alone. Side by side with me are countless others, striking for climate justice across every corner of the globe. We are the voices that will not be silenced—the wave of change that will not be stopped. We continue to strike to demand, to hope, and to choose to inspire.

But our unity is not just in our shared struggle. It is in our shared hope. I see a future where the lines of global inequality are blurred, where the Global South emerges as a beacon of resilience and sustainability—just like Ukraine. I envisage a world where the reign of fossil fuels is but a distant memory, where green renewable energies are the lifeblood of our progress. I hope for a planet where war is an archaic concept, back in history, where peace prevails not just among nations, but in nature itself.

I recall my journey: from the horrors of a war filled by fossil fuel energies to the front lines of the climate justice movement. I’m often reminded of a singular, profound truth: change is born from the womb of despair. In my despair, I discovered resilience. My experiences in war were a dark canvas upon which I painted a brighter future—not just for myself, but for my friends. I continue my activism because the war has taught me the devastating price of indifference and inaction, and it has shown me the way systemic greed can shatter lives and fracture societies. But it has also taught me that we are the architects of our destiny, our shared humanity, our capacity for empathy and innovation. These qualities must be channeled to create a world where prosperity doesn’t come at the cost of our planet.

Why do I continue to strike and protest, to lend my voice to this global chorus? Because history has shown us time and time again that it is through collective action, through the power of the people, that transformational change has been achieved. From the struggles of civil rights to the fights of women’s suffrage, collective action has been the shared price of justice: the demand for equality that has moved the machinery of progress. I strike for climate justice because I believe that our voices can cut through the noise of political discourse and corporate manipulation.

Our strikes are not just pleas for change: they are demands for it. They serve as a reminder to those in power that they are accountable to us now. Because when it’s too late, there will be nobody left to hold accountable. When I look at the climate strikes around the world. I see not merely a series of protests, but a global awakening. I see young and old, rich and poor, from every background, every nation, united by a shared understanding of the existential crisis we face. Each strike, each voice, is a testament to our collective commitment to steer our world away from the path of destruction. However, this global response must translate into global action. It is not enough to acknowledge the climate crisis: we must collectively confront it. We must hold our leaders accountable for their promises and push for ambitious climate policies. We must strive for a just transition, ensuring that the burden of change doesn’t fall on the most vulnerable among us.

Thank you.